When it comes to keeping athletes at the top of their game, the importance of good nutrition and physical conditioning are well-known.

In contrast, and despite being another vital factor, the importance of sleep is often underplayed.

But failing to take sleep seriously is bad news for sportspeople, because research shows that it can have a dramatic effect on performance. According to numerous studies, sleep improves an athlete’s motor skills, while regularly getting 6 hours a night or less dramatically increases the risk of sports injuries.

Given that many of our clients are athletes and fitness enthusiasts, Complete Pilates wanted to find out from an expert how sleep affects athletic performance.

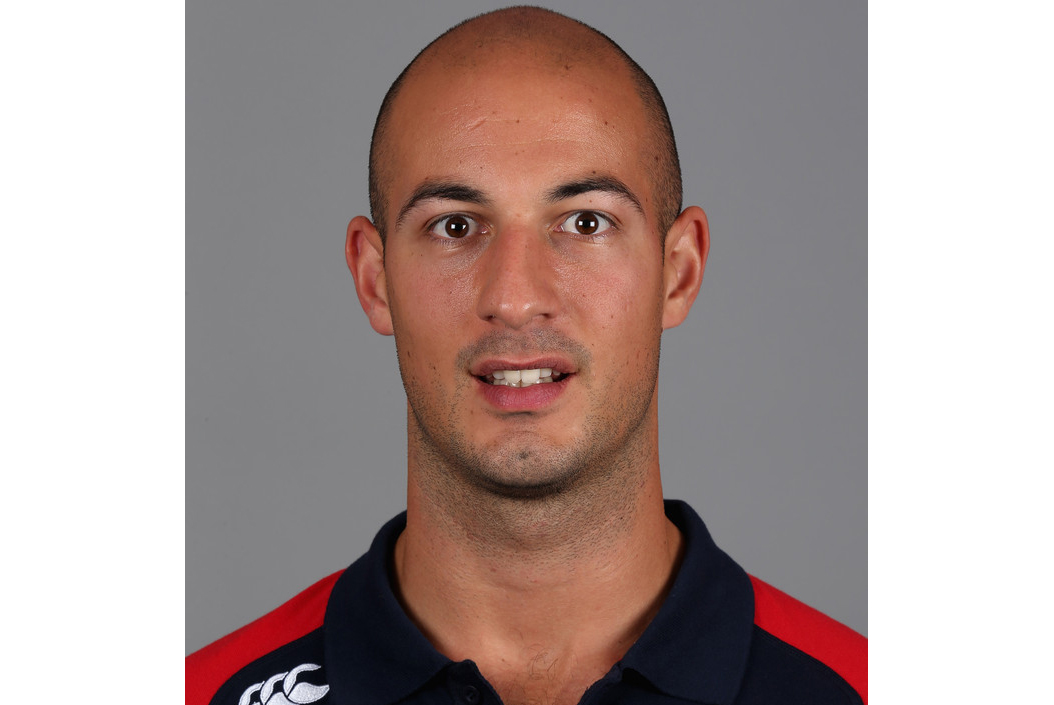

So we turned to Remi Mobed, elite sports Physiotherapist and specialist in this field. Mobed has worked with the Football Association, Cirque du Soleil and now the England Rugby Sevens where he implements his sleep research.

Q. You’ve conducted research into the connection between sleep and sports performance – how did you come up with the idea for it?

My sleep research idea came about when I was working for Cirque du Soleil as a Physio. In Cirque, every 7 to 8 weeks, we were travelling vast distances across the globe. Then we were expecting our athletes to perform 7 or 8 days after arriving there.

At the same time as working for Cirque, I was also doing a Masters assignment on sports people who travelled from one area of the globe to another area of the globe to participate in competitions. [It was through this] that I started to gain an interest in the effects of sleep [on sports performance].

My next job was with England Rugby Sevens, who really do travel vast distances. They travel from London to Dubai, Cape Town, Hong Kong, Singapore and New Zealand, meaning there is massive travel involved in their sport. When I came to Sevens, my role was to help the team travel better to then hopefully perform better.

Q. What did your sleep research involve?

We [myself and professors from Bath and Oxford University] got the Sevens players to wear actigraph wrist watches on a daily basis as well as when we travelled to New Zealand, which is the furthest travel we do.

Actigraphs are just over the counter wrist watches that contain small accelerometers which measure movements. From that they then estimate how much a person has slept.

Daily, I would then ask [the athletes] a series of subjective questions. They were blinded to the study, so they weren’t able to see how much they were actually sleeping as devised by the watch. I wanted to see how quickly they perceived they were recovering and how much they perceived they were sleeping from their own subjective experience.

Q. What were the results of your research?

It came up with some interesting results. Firstly, that athletes tend to recover more quickly from jet lag than normal people – I know this because I got the management to do the same study!

The study also told us how long our athletes generally took to recover and when our athletes were suffering most from jet lag.

Q: What exactly is jet lag?

There is a two-process model of sleep and wake regulation this is driven by homeostasis and our inner circadian rhythm, which lasts approximately 24 hours.

The SCN [a tiny part of the brain called the suprachiasmatic nucleus] is basically the computer within the brain responsible for maintaining this 24-hour circadian rhythm and for making us feel tired when it gets dark.

When we shift either forwards or back when we travel, there is a shift in our circadian rhythm. This is what jet lag is: a desynchronisation between the light/dark cycle and our circadian rhythm.

Most people can generally cope with a two-hour shift in either direction without it having a negative effect. That means if we go somewhere plus 2 hours or minus 2 hours we generally won’t recognise the effects of jet lag. However, any more than that takes 1 day per hour to reregulate your circadian rhythm to be on the level with the time zone.

That means for an athlete, if they’re traveling to New Zealand, that’s generally 10 days – a day per hour – for them to shift their circadian rhythm to New Zealand time. The same goes for if you’re going to New York, but minus 6 hours.

Q: What are the symptoms of jet lag?

As well as insomnia, symptoms of jet lag include fatigue and stomach problems which will persist when you land in a new place until your body has adapted to the next time zone.

Everyone adapts individually to the new time zone and it really depends on your own personal circadian pacemaker.

Q. How do you combat the effect jet lag has on your athletes?

By making the [circadian] shift occur quicker.

How do we do this? Well, about two or three days before travelling, we start exposing our athletes (or not, depending on where we are going) to blue light. We’re either trying to advance or delay their circadian clock, so we get them up earlier or later two to three days prior to travel.

On the flight, we generally don’t eat the plane food which is full of salt, which can make [stomach] problems caused by jet lag worse. We bring our own organic food and keep hydration levels high.

Exercise definitely helps you reset your circadian clock. But we recognise that when we first land that there is a huge risk of injury.

So, we alter our training programmes to make sure they are sufficient to get our athletes back on to a rhythm that is on the new time. Generally, that means mobility classes, low-level classes in the pool or on the bike, and as much exposure to day light as we can manage. We don’t put any of our high-risk contact sessions in until later in the week.

Q: Is it the lack of sleep that increases the risk of injury?

No, it’s not just the jet lag side of things where someone will be a lot sleepier.

Having been in a seated position for a long period of time, backs will be stiff and immobile so movement patterns won’t be the same. Tissues will also shorten.

Q: Should non-athletes also adjust their training habits when the fly long distances?

[Travel] will affect a non-athlete as much as an athlete. They should be using all the methods that athletes do.

Q: Do you monitor how much your athletes are sleeping on a daily basis?

We do daily monitoring with our athletes and keep their training in line with what we find from their results.

This includes measuring their HRV (heart rate variability), which is an objective measurement of how well they are recovering. So, we look at the neural system, their immune function, as well as how well they sleep.

[Our research showed that] the athletes were good at predicting their sleep, so we have them fill out a small questionnaire which aims to show how recovered they feel. It includes questions on their level of soreness, how well they feel, how well they think they’ve slept and how much sleep they’ve had.

Studies show that an athlete’s performance won’t be affected after just one night’s bad sleep – it’s the accumulative effect of lots of nights of bad sleep that’s the problem.

Q: How much sleep should both athletes and non-athletes be getting?

We should be looking to get at least 7 hours a night, which is 4 to 5 complete cycles [a sleep cycle lasts about 90 minutes] of sleep.

Having said that, when talking about sleep everyone gets fixated on a number. Everyone tends to focus on quantity rather than quality.

But the truth is, you can have 8 hours sleep and wake up and still feel like you’ve not slept at all – this is because sleep is about quality as well as quantity.

Together, quality sleep of the right quantity is what will give you access to the many benefits of sleep.

Want to get better quality sleep? Why not book an appointment with us and see how exercise really does help.

Education is key:

These blogs are designed to give information to everyone, however, it is important to remember that everyone is different! If you have not seen one of our therapists and have any questions about injuries, what you have read or whether this may be useful to you, please just ask. We are more than happy to help anyone and point you in the right direction. Our biggest belief is that education is key. The more you understand about your injury, illness and movement, the more you are likely to improve.